By: Ralph C. Freibert, III, MBA, CLU®, CLTC®, CIMA®, CFP®, Investment Advisor Representative

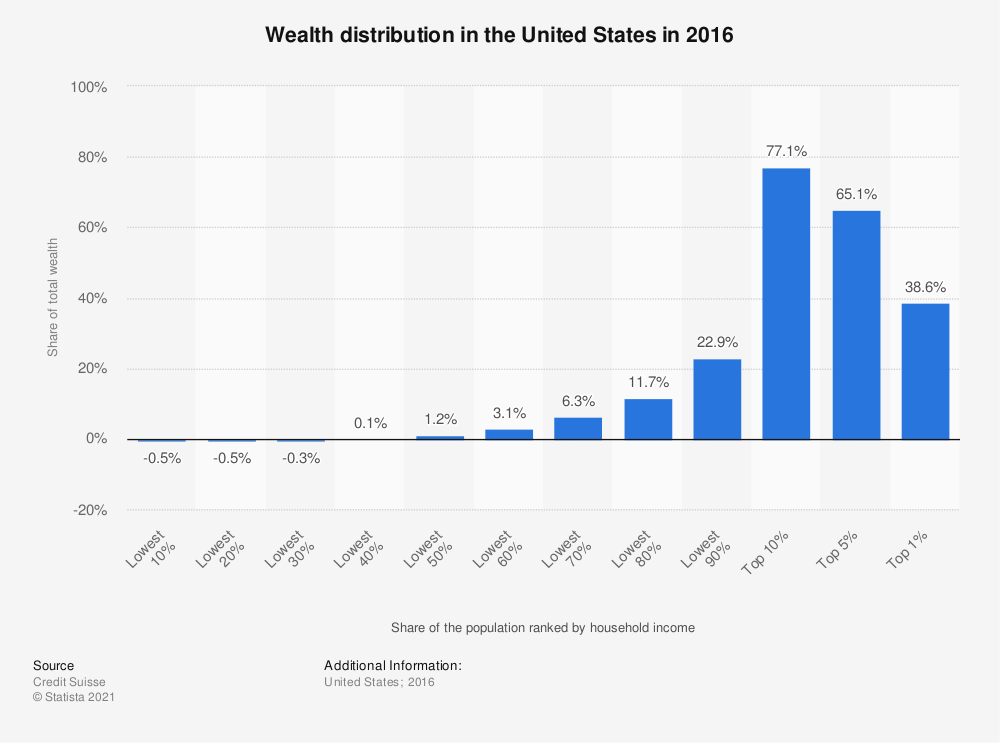

Ever wonder why so few succeed in wealth creation? Seventy-seven percent of the wealth in the United States is owned by just 10-percent of the population (see table below). Many would argue that this is a result of unequal opportunity, but people succeed from all races, backgrounds, regions, and religions. Financial success can be a result of a good idea (invention), luck (lotto winner), a new business (entrepreneurial spirit), or simply saving and investing.

In my 35-year career, I have met average individuals who have amassed wealth (over $1 million) simply by being disciplined in their behavior in relation to money and financial management.

Behavioral Finance (Behavioral Economics) is a field of study principally concerned with how human behavior affects market and individual financial outcomes. Unfortunately, more than fifty years of study has shown that our evolutionary make-up is simply not designed for investing and financial success. In fact, it runs contrary what is needed for success. That’s why understanding our programming can help anyone succeed overtime.

We are programmed with the “fight or flight” response to dangerous situations. This was a survival instinct when in the wilderness. However, today we are not faced with being eaten by a predator. We face potential relationship break-ups, job application rejections, and investment losses. All scare us and often lead to poor decision making. These events will not typically lead to death, but our bodies cannot distinguish the difference between a physical threat and an emotional one. Our blood pressure rises, we begin to sweat in a cooling effort, and we get ready to run, but it is hard to run from stressful events. Therefore, many find escape activities, such as: drinking, drug use, sleeping, movie watching, excessive exercise, shopping, and other avoidance behaviors.

When it comes to money and investment decisions, we are simply wired to make mistakes, whether is it overconfidence, loss aversion, hindsight bias, recency bias, mental accounting, or herding to name a few of the behaviors we seem to exhibit when dealing with money. In the following few paragraphs, I will highlight how these behaviors can work against you and potentially keep you from reaching your long-term financial goals. I will also provide some ideas for dealing with these biases in hopes of overcoming or at least minimizing their impact.

We all experience these biases. I have been a professional in the field of economics and finance for 35-years and have experienced the effects of almost all the biases. On occasion they have led to financial mistakes. If after reading this you feel immune to these biases, then I suggest you read more about “Overconfidence”. Not surprising, this bias is particularly prevalent in males (Yes ladies, I know…Duh!). Overconfidence can result from simply thinking you are better than you are and not acknowledging the impact of luck or help received from another in an outcome. There is an old saying, “it is better to be lucky than good” and that is true. But, when you start to feel outcomes are much more a result of being good, bad things tend to happen. Years of accumulation can be wiped out simply because of a “sure thing” or “I can’t lose” mentality.

Hindsight bias tends to support Overconfidence, since we tend to look at past events and say, “I knew that was going to happen”. Hopefully, this will not come as a surprise, but we really have no ability to predict the future. If something seemed to be on the horizon and we thought about it, that was just a thought, and the outcome was mostly a random occurrence. But our minds tell us, “You knew that!” If the outcome was truly expected and predicted, then why was no action taken?

Recency bias, results when we give more weight to recent information than to past information. It is as if the new information is more accurate and better, but typically new information tends to be flawed by error and carries no more weight than that of past events. This one entertains me the most when talking with others. They say, “Can you believe how much the market is up/down?”, but that is based upon recent news. Perhaps the market is up over the past month, but it could also be down for the year if there was an early decline. Unfortunately, news is just that. Whether old or new, weight should be given to the news that is most accurate and trustworthy. If new information provides new conclusions, then it should be considered, but it is much better to look at long-term data or more heavily weight information that has been supported by multiple credible sources to draw conclusions. We live in a sound bite, immediate, world where what is going on today is most important. Unfortunately, saving and investing is a long game won over, not years, but decades.

Herding and Confirmation bias are two other mental errors that can lead to big financial mistakes. Herding is exactly what you might think. We tend to follow the crowd even when the crowd is no more knowledgeable than we. This is very true in investment analysis. Analysts tend to not deviate too much from what other analysts are saying about a particular company, because if wrong they would rather be in the company of others. Confirmation bias is similar but not the same. We tend to weigh information that supports our beliefs and discount information that is contrary. The funny thing is, we should be paying more attention to contradictory information to avoid making mistakes.

Loss Aversion is one of the worst biases as it can be most costly to an investment portfolio. Daniel Kahnemen and Amos Tversky published a paper in 1979 titled “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk”[1] which posited the theory that we feel the pain of losses more greatly than we feel the pleasure of gain. This can lead to all kinds of decision errors, such as selling at the bottom a market event or buying at the top of a bubble. Yes, Herding and other biases come into play here and when they work together, we see behavior that lacks rational judgement.

But despite these biases and the millions of years of evolutionary programming, they can be overcome. The circuits that wire our behavior can be shorted and more sound behavior established. But it does require effort and courage, and most important, projecting (not prediction) into the future.

The first step is to recognize that unless you have a PhD in economics, finance, or physics (perhaps all three), you are not likely to make better decisions about money and investment than the average person. Illusory Superiority effect tells us that most of us believe we are better than average at a host of things, but we cannot all be better than average. This effect continually shows up in psychology studies and is just our natural tendency.[2] I have studied the economy, markets, and investments for over 35 years, and I have limited confidence in my ability to predict specific market actions and investment returns, and research says that most people are in the same boat as me. However, there are things we can predict, such as spending less money than we earn leads to savings; equity markets tend to go up over long periods of time simply because of business production and normal inflation; and, recognizing there is nothing that is a sure thing. Consistent purchase of equity indexes will build wealth over time.

Another step is to follow sound investment principles, such as holding enough reserves for emergencies, and diversifying your investment holdings. This avoids the need to sell assets in periods of decline. Unfortunately, few people have true reserves and diversification for many simply means having a lot of different investments.

I often ask, “Do you save emergency reserves?”, and I the answer is often, “Yes! I save $500 each month for my annual vacation” or “I am saving $250 per month for a new car”. Unfortunately, that is called “Deferred Spending”. Reserves are the funds allocated for emergencies. They are the fire ax behind the glass with the words, “Break glass only in an emergency”. Diversification is the process of holding different investments that are not highly correlated, so when one is up or down the other is acting differently. I see portfolios that hold five or six different stock funds, but those funds have many of the same investments or are in similar markets. A diversified portfolio holds assets in different markets and different styles which typically move up and down at different times and different magnitudes.

Finally, recognize that if everyone is doing something and making lots of money, you should be skeptical. Something must be up! Herds do provide some protection against predators, and even in investing the momentum of the herd can carry markets higher, but without a clear direction the herd can and sometimes does go off the cliff with the followers just as impacted as the leader. If you are doing something simply because someone else is doing it, you really have no strategy nor decision making framework to operate independently. If you lack experience, then stick to the basics of investing because they really are simple. When we work with clients who lack investment sophistication, we keep portfolios basic and educate them before adding complexity.

Personally, I seek out information that is contrary to my beliefs. If I cannot support my beliefs against opposing views, then my view is likely flawed. Additionally, I only participate in savings and investment programs that I understand. Often, I meet with people who say, “I don’t understand investments and markets”. My answer is, “Basic investing is not complicated. If you don’t understand basic investing, then it is critical that you learn, even if you have an advisor, because chances are they don’t understand, or worse, follow, basic investing principles either”.

We all have biases. As I stated in my introduction, I am no different than anyone else. The key however is to recognize these biases and how they shape our decision making. If we recognize our tendencies, then we are much more likely to minimize their impact by slowing our thoughts and asking additional questions.

[1] [1] “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk”, but Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, Econometrica, March 1979.

[2] “Why We Are All Above Average”, by Tia Ghose. https://www.livescience.com/26914-why-we-are-all-above-average.html

This commentary reflects the personal opinions, viewpoints and analyses of Planning Associates Wealth Management, LLC employees providing such comments, and should not be regarded as a description of advisory services provided by Planning Associates Wealth Management, LLC or performance returns of any Planning Associates Wealth Management, LLC client. The views reflected in the commentary are subject to change at any time without notice. Nothing in this commentary constitutes investment advice, performance data or any recommendation that any particular security, portfolio of securities, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. Any mention of a particular security and related performance data is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Planning Associates Wealth Management, LLC manages its clients’ accounts using a variety of investment techniques and strategies, which are not necessarily discussed in the commentary. Investments in securities involve the risk of loss. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Recent Comments